In her classic memoir, Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys, Viv Albertine recounts not only the time she spent as a punk during the 1970s in her pioneering band the Slits, but also documents her life after the band had ended. This is unusual. Most music books don’t venture into this territory, tending to stop when the hits stop, thereby drawing a veil over what happens next. The unspoken suggestion seems to be that, were it to continue, the story would descend helplessly into misery memoir.

“The pain I feel from the Slits ending is worse than splitting up with a boyfriend,” Albertine wrote, “This feels like the death of a huge part of myself, two whole thirds gone … I’ve got nowhere to go, nothing to do; I’m cast back into the world like a sycamore seed spinning into the wind.”

I loved Albertine’s book, and it was this one paragraph in particular, I think, that propelled me into writing my own book on this very subject: the curious afterlife of pop stars. I wanted to know what it’s like when that awkward next chapter begins, where anonymity replaces infamy, and the ordinary reasserts itself over the extraordinary. The life Albertine forged for herself after punk was complicated, as life tends to be. She returned to education, studying film; underwent IVF; and endured both illness and divorce. But she never fully let the music go, because musicians mostly don’t; they can’t. I finished her book convinced she was a hero.

Sign up to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly highlights

But then perhaps all pop stars are? They’re fascinating individuals, compelling and gifted, not short of self-confidence and, yes, occasionally a little odd, too. Artists may not always be the best people to operate the heavy machinery of adulthood, but they remain tenacious, driven and inspirational. They dared to dream, and then went out and made that dream come true.

But falling back down to earth, in this business, is an inescapable certainty. Like sportsmen and women, they peak early. A songwriter once told me, citing Bob Dylan, that “artists tend to write their best songs between the ages of 23 and 27”. Despite his enduring success, Dylan has suggested he couldn’t write the songs he wrote in his 20s in his later years, at least not in the same way or with the same instinct, largely because, after that early momentum has fizzled out, things settle down into simply the thing that you do, with all the humdrum ennui associated with that. So what’s it like, I wondered, to still be doing this “job” at 35, and 52, and beyond? What’s it like to have released your debut album to a global roar, and your 12th to barely a whisper? Why the continued compulsion to create at all, to demand yet more adulation? Frankly, what’s the point?

And so, armed with a batch of potentially indelicate questions – because who likes to discuss failure? – I began to reach out to musicians from various genres and eras, those who hadn’t died young, but were still here, still working, to ask them what it was like in the margins.

A great many never bothered to respond. Others enthusiastically agreed, only to later bail out. The guitarist from one of America’s most stylish modern rock acts, someone whose skinny jeans no longer fit quite as well as they used to, was initially keen, but cancelled at the last minute because, his manager informed me, “his head just isn’t in the right place to discuss this right now. It’s a difficult subject.” Those who did speak, however – 50 in total, from Joan Armatrading to S Club 7; Franz Ferdinand to Shirley Collins – were endlessly revealing and candid in a way they would never have been at the peak of their fame. I sensed they enjoyed the opportunity to talk again, to be heard above the din of Ed Sheeran and Adele and Stormzy. All were humble, replete with wisdom, resolute. (Many were divorced, too; at least one was high.)

They’re the true Stoics, I realised. We could learn a lot from them.

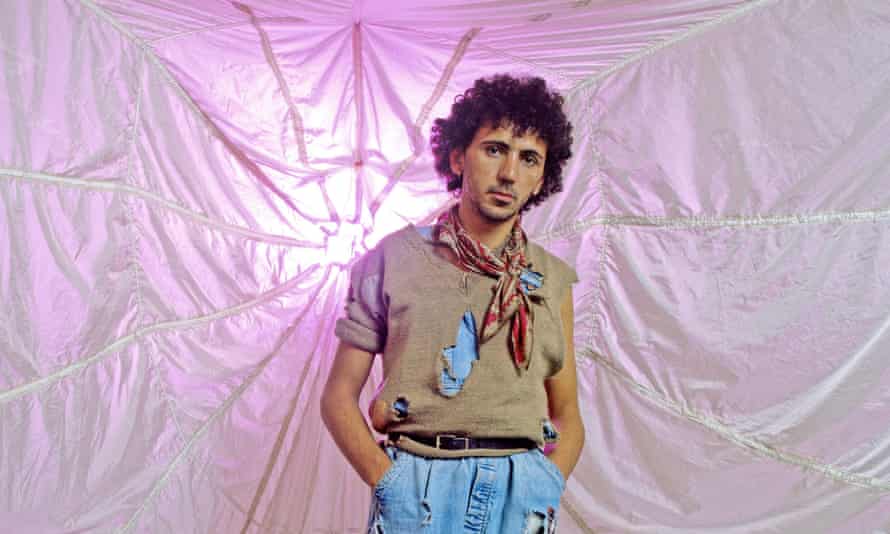

Each individual story in popular music has a common beginning. Because in the beginning, all is gravy. In 1987, seemingly overnight, Terence Trent D’Arby became the most arresting new pop star of his generation. To hear him sing songs such as If You Let Me Stay and Sign Your Name was to bear witness to the art of aural seduction; the knees buckled. He became terribly famous, terribly quickly. He was 25.

“I wanted adulation and got it,” D’Arby tells me almost 35 years later, by now working under the name Sananda Maitreya, “but I had to die to survive it.”

If his ascendancy had the stuff of legend about it, then so did his demise. Like Prince before him, he began to feel himself capable of anything, each new song he composed a masterpiece. His record company felt differently – it wanted hits, not ornate rock operas – but D’Arby was not someone easily restrained. And so, in pursuit of his muse, he spent the early 90s reportedly living the life of a tormented recluse in a Los Angeles mansion. When I speak to him – which takes six months to arrange – he suggests he was grateful to move on “from such excess and artifice. I didn’t give a fuck about it then, and even less about it now that memory has been kind enough to allow me to forget most of it.”

Prince had died, Michael Jackson, too. D’Arby was still here, albeit with a name change – prompted by a dream he had in 1995 – to help him better bury the past. Today, Maitreya lives in Milan, is happily married with young children, and writes, records and produces his own music, which he releases on his own label, behaving as he damn well pleases. In 2017, this meant issuing a 53-track album with at least one song dedicated to a first-hand experience of impotence. “I’m a fellow who likes to drink and smoke/It used to once hang down to the tops of my shoes/Now all I’ve got is these limp dick blues.”

The question of whether anyone is listening any more doesn’t seem to trouble him unduly. When I ask what, if anything, he misses from the old days, he replies: “I miss the unbridled, bold, naked stupidity of youth’s vibrant electric hubris.”

During the same era, Kevin Rowland found himself in a comparable position. “I’d been too confident, too arrogant,” the Dexys Midnight Runners singer says. “I thought everyone would hear our new music and go: ‘Wow.’”

The fact that they didn’t, not any more, left him bewildered. Dexys were one of the more brilliant bands of the 80s, with a slew of hits, several No 1s and an eternal classic in Come On Eileen, a song legally required to be played at every wedding disco on mainland Britain ever since. But by the end of that decade, Rowland wanted to develop his craft, and leave boisterous singalongs behind. His label, and quite possibly some members of his own band, simply wanted more of the same. It wasn’t broke, so why fix it?

But, Rowland tells me, “I just knew that I couldn’t write the same songs again, and so I never even tried.” Their new music took on an increasingly introspective tone, mournful and ruminative; not ideal for radio, in other words. The band were dropped, they split up, and the singer found solace in drugs. Whatever money he’d made was soon lost, and before a stint in rehab came the need to sign on: a profound humbling. At the dole office, his fellow unemployed recognised him and broke into a rendition of Come On Eileen, half hoping he’d join in. “I could have done without that,” he notes.

The passing of fad and fashion is rarely the artist’s fault. In a 1997 piece for the New Yorker, the American essayist Louis Menand suggested that stardom cannot last longer than three years. “It is the intersection of personality with history, a perfect congruence of the way the world happens to be and the way the star is. The world, however, moves on.”

To her credit, Suzanne Vega tried to move with it. It was 1990, and by this stage she’d enjoyed huge success for three years. This was no mean feat, because her unadorned acoustic songs stood in direct contrast to the more brash preoccupations of pop in the 80s, a time when Madonna ruled. “But by 1987,” Vega recalls, “every door was open to me, every gig I did sold out.”

And so, in 1990, she announced her most ambitious tour yet. Rather than her usual requirements of an acoustic guitar and a single spotlight, she now had “a set designer, trucks and buses, a crew, a backing band; catering, a backup singer, a woman to do the clothing. This was a big deal for me.”

On the tour’s opening night in New York, the venue was just a third full. “I thought: ‘Where’s the rest of the audience? Maybe they’re still out in the lobby?’”

There was no rest of the audience; they’d already moved on. Vega herself had done nothing wrong here, but rather done things a little too right. The industry had taken note of her earlier success, reminding them of the marketable power of a singer in touch with her emotions, and so had invested in a new batch: Sinéad O’Connor, Tanita Tikaram, Tracy Chapman. These artists rendered the scene’s godmother abruptly superfluous.

Vega’s tour, haemorrhaging money, was cut short. When she arrived back at JFK, she looked out for the car her record label would always send to collect her. But there was no car. Not any more.

“I took a taxi,” she says.

But Vega, like Maitreya and Rowland, didn’t throw in the towel simply because others had come along to steal her thunder. She simply, and by necessity, pivoted towards cult status, which at least came with the safety belt of a loyal fanbase that still sustains her today. There are benefits to staying in your lane. “Would I like another hit?” Vega wonders. “I wouldn’t say no, but I’m not going to chase it.”

The writing on the wall is only easy to read in hindsight. At the time, it’s all a blur. I approach the wiliest of pop provocateurs, Bill Drummond of the KLF, an act that, at the height of their success in 1992, disbanded and then deleted their entire back catalogue with the sole intent of swiftly disappearing up their own fundament. When I ask him what an artist should do once the spotlight swings elsewhere, he writes me a play – or rather, two, “in case the first one’s shite”, he helpfully explains. The plays reference Prince and 80s hitmaker Nik Kershaw, and the way both leaned on the public’s endless appetite for nostalgia in order to stretch out their careers. Drummond prefers a more flamboyant gesture: the very moment any singer fails to crack the Top 40, they should offer themselves up for sacrifice. “The failed pop singer will be given the choice of a noose hanging from a gallows or a razor-sharp guillotine,” he writes.

This may well suit self-sabotaging provocateurs, but other artists have less appetite for creative suicide. It is true, though, that a future of looking back, of existing solely on nostalgia, is a creative cul-de-sac, an eternal Groundhog Day where China in Your Hand is No 1 for ever. Steps should be taken to avoid such a fate.

When Mancunian stalwarts James, for example, split in 2001, frontman Tim Booth moved to northern California, where he became a shaman and studied the practice of “consciousness expansion”. He only rejoined the group on the condition that they wouldn’t become a heritage act, “which for me is the kiss of death”. After singer Róisín Murphy had navigated the end of her pop duo, Moloko, and then attempted to steer an idiosyncratic solo career with a determination Orson Welles might have admired, she moved to Ibiza to focus on two things: motherhood and the Mediterranean. “Sometimes it’s nice to just relax, you know,” she says.

Billy Bragg realised he needed to take a pause from his career in 1990, once Margaret Thatcher had been toppled. Bragg’s antagonism towards the former prime minister had been his whole raison d’être, after all. With her gone, what then? “It was time for a rethink,” he tells me. He got married and had a child, and later eased himself back into music, by then sporting a beard and plying the kind of alt-folk that would allow him to both age gracefully and bring his fans – who were also ageing – along for the ride. Occasionally, he writes comment pieces for the Guardian, largely to keep the spark alive. He still pops up on picket lines, too. Why? “Because I’m Billy Bragg, that’s what I do.”

If all bands crave headlines in their early days, then So Solid Crew achieved all the wrong ones. It became increasingly easy to overlook the musical achievements of the first UK garage act to break through into the mainstream back in the early 2000s because what happened off stage became far more compelling. Several live shows were blighted by violence, while members G-Man and Asher D – the latter to find fame later as the Top Boy actor Ashley Walters – were arrested for possessing handguns. Once So Solid imploded, its sole female member, Lisa Maffia, a single mother, needed to start earning again, as she’d spent everything she’d accrued. “Three cars in the driveway, so much jewellery, clothes in abundance! Limousines!” she recalls. She launched a short-lived solo career, record label and clothing line, but her “brand” appeared in terminal decline. So she started her own booking agency, with herself as the sole employee, calling up clubs across the country masquerading as the personal assistant to one Lisa Maffia, formerly of So Solid Crew, now an international solo star and occasional fashion designer. Her PA, “Celine”, was tasked with asking clubs’ management if they’d be interested in a personal appearance.

“The bookings came in almost immediately,” Maffia beams. “I hustle. Never been afraid to hustle.” She now runs a beauty salon in Margate.

Maffia has achieved what many former pop stars don’t, and what Albertine for a long time couldn’t: replacing one satisfying career with another. The majority find themselves instead with an embarrassment of yawning time on their hands: how to fill it?

Some I speak to use that time as an opportunity for personal growth. David Gray and the Darkness’s Justin Hawkins discuss the growing conviction that they might have autism and ADHD, respectively, both convinced this played a key part in the art they made. “I love upheaval, I love emotional disasters, and mismanaging every relationship I’ve ever had,” Hawkins suggests, which sounds less like introspection than a robust embracing of who he is, sod the consequences.

When the Boomtown Rats abruptly reached their dead end in 1985, singer Bob Geldof wasn’t happy. He felt they still had so much more to offer, but it was Duran Duran’s turn now. Geldof slunk home, drew the curtains, “and I thought: ‘That’s it? It’s over? Had the best years of my life already passed? I was 30. What a brutal business pop music is.”

It was during a quiet night in – when, by rights, he should have been straddling a microphone stand on a stage somewhere glamorous and, crucially, far away – that he happened on Michael Buerk’s report from a famine-ravaged Ethiopia on the news. This gave him an unexpected new focus, but here’s the thing: even after feeding the world, and, later, a hugely successful career in business (launching the TV production company Planet 24; investing in tech), all Geldof wanted to do was to go back to music. In 2020, the Boomtown Rats, average age then 66, released a new album.

“In my passport, my profession is listed as musician,” says Geldof, “not saint.”

The Boomtown Rats reformed because bands do. It’s practically mandatory. When Tanya Donelly, of 90s US indie darlings Belly, quit after winning a Grammy (and promptly suffering burnout), she craved normal work and became a doula. When 10,000 Maniacs’ Natalie Merchant grew tired of being a marketable commodity, she quit for the quieter life of a solo artist, and was then duly horrified when her debut album, 1995’s Tigerlily, sold 5m copies, because “then came the treadmill again”. The next time she tried to retire, she did so more forcefully, and now teaches arts and crafts to underprivileged children in New York state. “I look at people like Bob Dylan and Paul McCartney,” she says, referring to the way both legends continue to tour, “and I think to myself: ‘If I were you, I’d just go home and enjoy my garden.’ It’s a question of temperament, clearly.”

And yet, just as Donelly would ultimately return to her old band, Merchant is also entertaining the idea of new music. “Maybe,” she says. “My daughter is off at college now, so I do have more time to myself … ”

But why? Why do they all come back? Perhaps because nothing else compares. It must be nice to be quite so loudly loved.

Even those who were scarred by their experiences still curiously hanker after it. Child reggae stars Musical Youth were a ray of early-80s sunshine when their single Pass the Dutchie sold 5m copies around the world. Once their fame elapsed, and it did so with breathtaking speed, one member, Patrick Waite, developed drug problems, turned to crime, and died of heart failure at 24. Another, Kelvin Grant, became a recluse; singer Dennis Seaton a born-again Christian. “It saved me,” he tells me. Now in his mid-50s and a father of four, Seaton is the chairman of the Ladder Association training committee, alerting builders to the dangers of working at altitude without sufficient protection. “Which is funny, I know,” he shrugs, as if the idea of a former pop star now doing an ordinary job boggles the mind. At weekends he still tours nightclubs to sing his famous song to crowds of people who want nothing else from him and are simply grateful to be in his orbit. “To have touched so many people, let me tell you, is humbling,” he says.

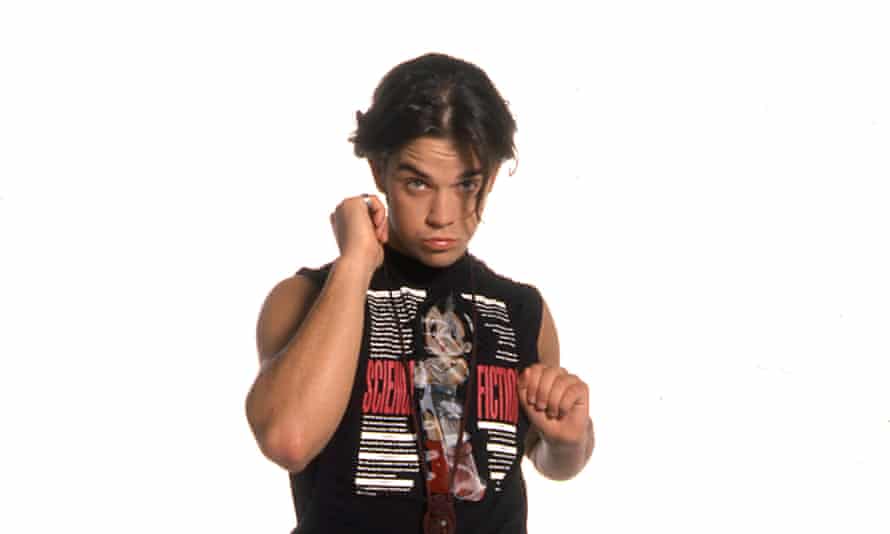

Robbie Williams sums it up well. “I felt very driven in the early days, in competition with the world and with myself.” He remains a big draw, of course, but 30 years in, he’s no longer guaranteed hits and is now more likely to be playlisted on Smooth Radio than BBC Radio 1. But that sense of competitiveness never fully recedes. He tells me the new songs he is writing are sounding like David Bowie and Lou Reed, experimental and avant garde, “But do I unashamedly want to still be one of the biggest artists in the world? Yeah, I do.”

And so he, and so many like him, linger in those margins, watchful for other opportunities, biding their time. They judge TV singing competitions and appear on reality shows, and wait for the world to turn slowly on its axis to bring them back into fashion. Eventually, everything comes back into fashion.

The midlife pop star’s best virtue, then, is patience, and the conviction that the best might be yet to come. “I’ve had an interesting first half of my life,” Williams notes. “I’d like an interesting second half, too.”

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/OFQYW4YXDJJQDA66QVBZN7QF7I.jpg)